Forest Service Chief Talks Need For New Fire Management, Fuel Treatments

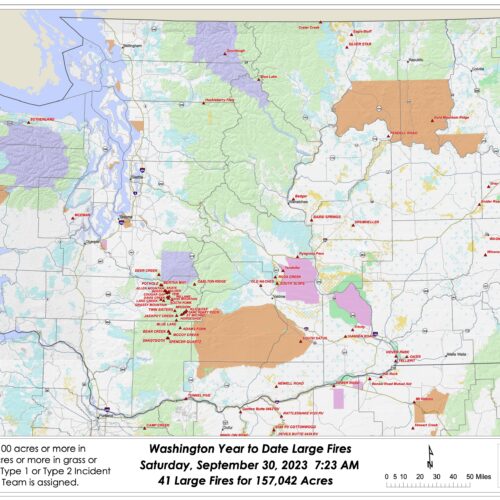

The West is in the midst of another intense fire season. Fires in California and Oregon have claimed lives and homes and burned up farmland.

As part of EarthFix’s ongoing series on wildfire, reporter Tony Schick spoke with interim Forest Service Chief Vicki Christiansen about what her agency is doing to reform fire management and reverse the fire problem.

Christiansen discussed her agency’s approach to wildfire management and what she’s doing to reduce the damage from wildfires in the future. Below are some of her responses on these issues, edited for length and clarity.

U.S. Forest Service Interim Chief Vicki Christiansen

CREDIT: U.S. FOREST SERVICE

As EarthFix reported, the Forest Service still suppresses nearly all fires, decades after recognizing the danger in that practice. Wildland fire agencies currently spend millions fighting relatively low-risk fires that could actually help protect communities if allowed to burn a bigger footprint. Researchers within the Forest Service are trying to push wildland fire management toward more data-driven decisions that consider the long-term tradeoffs of fire suppression. Asked what she’s doing to implement that throughout the agency, Christiansen said she was trying to build more acumen for risk management and reset the agency’s thinking.

“We are successful at extinguishing 98 percent of all fires. But there’s 2 percent that, I call them hurricane fires. We don’t ask public safety officials to stop a hurricane. We ask them to get people out of harm’s way, to provide assistance to mitigate, create resilience, etc. Well that’s the situation we are in. But we are asking many of our responders to take aggressive action when there is zero probability of success.

“So our reset is about thinking about (the) probability of success, and just the first line — all fire is bad and we must stop it. Why are we exposing responders, not doing our work to get people out of harm’s way, spending all kinds of public funds, when the probability of success is zero to very low. That’s the first level of the reset.”

Christiansen often talks about the agency’s 98 percent success rate at keeping fires small on initial attack. Researchers have pointed out that number, for many reasons, might not be the best measure of success for an agency with a stated goal of living with fire, not simply trying to extinguish it. Christiansen said the Forest Service would start to talk about metrics:

“There might be a day, a year, or four or five whatever it is down the road, where I don’t have to articulate just the 98 percent initial attack success rate because we’ve created more understanding, more acceptance of fire’s role on the landscape, where allowable.”

Christiansen said she pictures a system that better separates “wanted” and “unwanted” fire. Unwanted fire would still be measured by initial attack. But wanted fire would be measured based on how often it’s meeting certain objectives, like improving the environment, providing habitat and reducing risk to nearby communities.

“I hate to boil it down this way, but there’s good fire and bad fire. So, then we have shared goals about bad fire and we have some shared goals — and measure our outcomes — about good fire.”

The West is way behind where it needs to be for fuel treatments and many of the treatments being done do not follow what science has shown to be most effective, as EarthFix reported last week. Prescribed fire is a crucial aspect of fuels reduction and forest restoration, but its missing on a large number of projects. Asked what the agency was doing to make sure treatments keep pace, Christiansen said the West needs to adopt the culture of the Southeastern U.S., where burning is common practice:

“We don’t have a culture of accepting fire in the West like we do in the Southeast. The Southeast, it’s a part of the culture, of the community that you have to have routine burning to keep the landscapes in their most productive condition. So we have a cultural barrier and a lot of that leads to smoke, but that’s not the only barrier.

“The smoke management is a whole complex issue of itself. But as we have had more drastic, catastrophic wildfires, there is more public understanding that these landscapes need to burn somehow and if we can meter it out with some planning, with some advanced notice and over time in smaller doses, that taking our smoke in that way is better than multiple weeks if not months on end of being smoked out, as you all in Portland and throughout Oregon and Washington experienced last year.”

This year Congress stabilized Forest Service funding by ending its need to borrow from other accounts to pay for wildfire suppression. In stopping firefighting from consuming more and more of the budget, that should free up more of the agency’s money for things that could prevent large, catastrophic fires – like thinning out forests to remove fuels and prescribed burning. But Christiansen said she did not have specific goals yet for how to increase that work:

“No, because when we only talk about ‘X amount of acres treated,’ we’re not talking about outcomes. We want to work at the state level to talk about what are the most important outcomes. We have protection of watersheds, of critical communities. We want to keep infrastructure, milling infrastructure, open and create new milling infrastructure. I will absolutely guarantee it’s not business as usual.”

She also said not to expect results any time soon:

“I’m sorry to use the cliché but we are turning the Titanic. It’s more than 100 years of working our way to where we’re at now and it’s not going to turn around in a year or two. But we’re already seeing small differences where we are putting fuel breaks around communities. I have four examples that have come to me in the last two weeks where fuel breaks around communities absolutely stopped the fire from coming into these communities.

“We do know where we treat hazardous fuels and we go back and test if it changed fire behavior when fire came across it, 89 percent of the time it has changed the fire behavior or significantly protected critical access.

“It’s going to be a handful of years till we really see a significant change in trajectory on the risk curve. But if we don’t start now we’re never going to get there.”

Throughout the interview, Christiansen stressed that because of the intersection of land ownership throughout the West, the Forest Service, states, local agencies and private owners needed to keep moving past blaming each other for fire damage:

“As we saw the escalating fire on the landscape we know we had to stop pointing fingers. The state and the locals would point to federal land managers and articulate it’s your unhealthy landscapes and the feds would point back at the state and locals saying they weren’t managing or controlling all the growth in the wildland-urban interface. And we’d point to extended drought, etc.

“The point is, that we could have years of discussion about what percentage of each of those things contributed to the escalating fire situation that we find ourselves in, or we could put an frame on this: how are we going to spend our collective energy to try to change what we call the risk trajectory. We’re still on an upward risk trajectory, don’t get me wrong.”

Copyright 2018 Earthfix

Related Stories:

Oregon researchers hope to provide new tools to help wine growers address climate change, smoke

Pinot noir grapes at Oregon State University’s Woodhall Vineyard undergoing smoke experiments. (Credit: Sean Nealon / OSU) Listen (Runtime :54) Read Researchers are developing special coatings to protect Northwest wines… Continue Reading Oregon researchers hope to provide new tools to help wine growers address climate change, smoke

What impacts did wildfires have on the Northwest this summer?

Autumn has knocked on our doors and crossed our thresholds. With its arrival comes wetter, colder, darker days — perhaps some pumpkin-flavored treats as well — and hopefully, fewer wildfires. Heavy recent rainfall has dropped the wildfire potential outlook down to normal for the Northwest, according to the National Significant Wildland Fire Potential Outlook.

So, how did this summer fare compared to past fire seasons? Continue Reading What impacts did wildfires have on the Northwest this summer?

Fighting fire with fire: Bringing prescribed burns back to Washington state

As the days get hotter and warmer, many Washingtonians are gearing up for the wildfires that will ignite across the region this year, causing smoky skies, evacuations and potentially devastating loss.

Continue Reading Fighting fire with fire: Bringing prescribed burns back to Washington state